REVIEW: Battle Abbey

Is this where the Brexit vote came from? The spot where King Harold was slain by the invading Norman French 957 years ago.

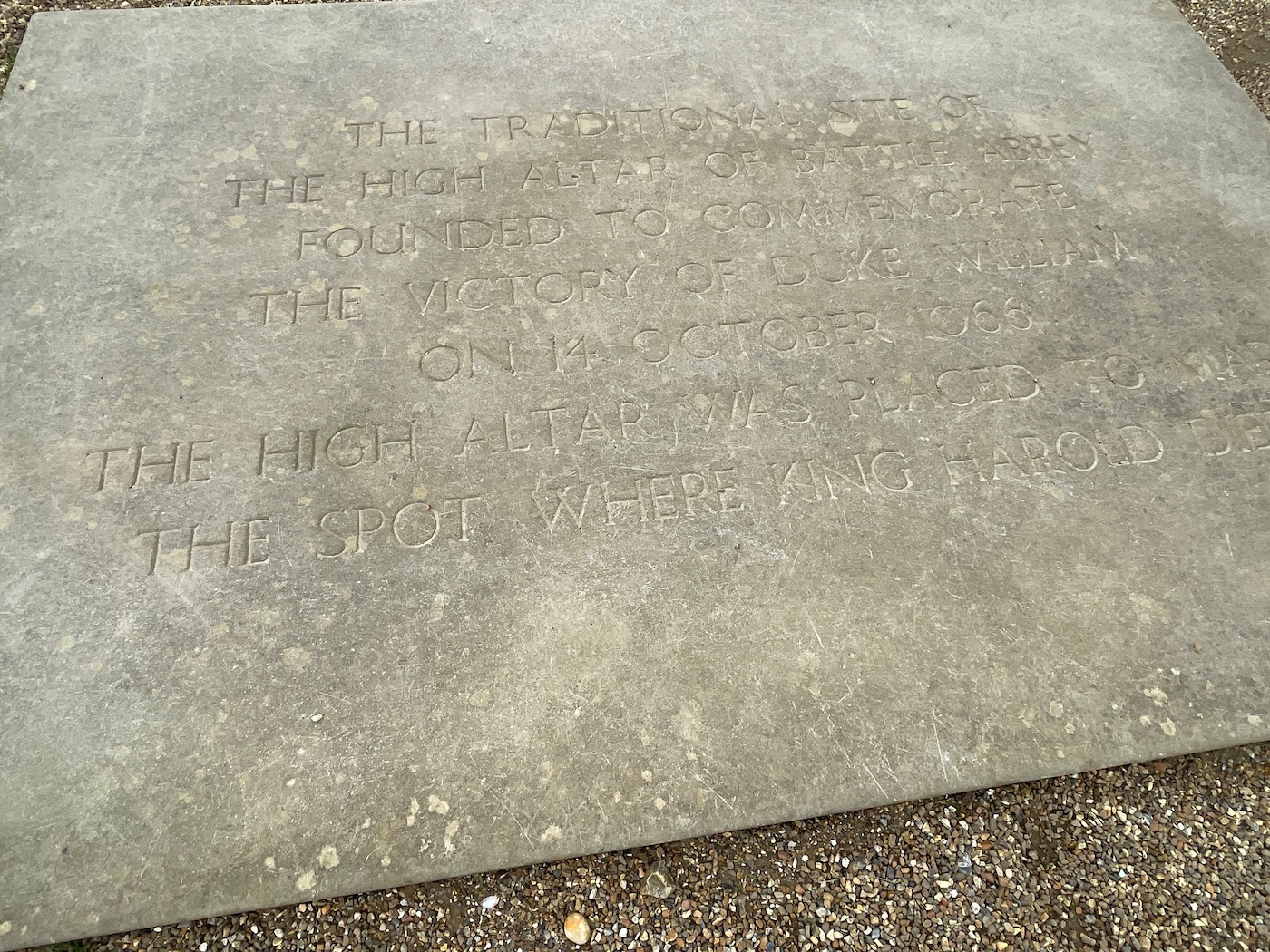

William of Normandy was respectful of where his enemy died, so a stone tablet marks the place.

Standing on the ridge of Senlac Hill, one strains to imagine thousands of Anglo-Saxon and French soldiers fighting in the bloody hand-to-hand battle.

It is fair to say that 1066 remains the most significant date in English history, marking the start of French rule for 300 years: the Normans followed by the Plantagenets.

This period laid the foundations of our modern parliamentary and justice systems. French rule also gave us one third of the ‘English’ language. Most of what we say using formal language is French, the basics tend to be Old English.

And the English language persisted, despite the fact that French was the language of power, court and nobility. It was used to record court proceedings, along with Latin, until 1362 when it was changed to English because not enough people understood French for a fair system.

Are these the kind of events which led to the apparent English ingrained suspicion of ‘foreigners’? Why we voted narrowly to leave the EU?

It’s something to reflect on as one stands at Battle Abbey, on the Victorian-built terrace which looks down the slope across the battlefield. Today, it is a delightful stretch of East Sussex countryside, cloaked in daffodils (above).

So why did the battle take place?

In January 1066, Edward the Confessor died. He had no children and had promised the throne to William, Duke of Normandy, a distant relative. However, on his deathbed he named his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, as his successor. William was infuriated and launched an invasion fleet across the English Channel, landing at Pevensey.

The Norman army numbered 7,000, nearly half of whom were mounted knights in armour. Harold’s army was a similar size but his soldiers were exhausted after several days’ march south from their victory over invading Norwegians at Stamford Bridge, near York.

War trumpets sounded on the morning of October 14, 1066, on Senlac Hill and battle began. Repeated assaults by Norman archers and cavalry on the wall of Saxon shields led to victory for William and death to Harold. William was crowned king of England on Christmas Day 1066.

William ordered that an abbey and Benedictine monastery be built on the site to commemorate his victory and those who had died. He insisted that the original higher ridge of the hill was levelled out for the buildings, however hard it was to construct on a hill nearly 1,000 years ago.

So began three centuries when French-speaking kings ruled English-speaking peasants.

The gatehouse of this significant site dominates Battle high street, where everyday life goes on amid independent shops and constant traffic. Few probably give much thought to what happened here almost a millennium ago.

If you’re feeling fit, you can wind your way up the stone stairs to the top of the gatehouse (above) and far-reaching views across the town and surrounding countryside, as far as the sea on a clear day.

One of the most striking buildings is the chapter house, completed about 1100 (below left), which contained the monks’ dormitory and latrines. One towering end and part of the side walls remain, dominating the battlefield below.

The vaulted novices’ chamber (below right) is atmospheric and shadowed with the pillars beneath the arching ceilings.

Many parts of the site comprise later additions: the terrace runs alongside the remains of a 13th century monastic guest quarters and two striking 16th century towers.

In 1538, Henry VIII gave Battle Abbey to one of his close friends who demolished the church, chapter house, refectory and cloister walk.

It later became a centre for Catholicism, which was illegal at the time, before being owned over the next few centuries by various nobility.

By 1922, some of the abbey buildings were leased to a private school, which still occupies them today. The estate was bought by the government in the 1970s and is now cared for by English Heritage, a charity that manages more than 400 historic monuments, buildings and places.

Battle Abbey is a beautiful site to wander around, photogenic from every angle, steeped in history at every step.

Free guided tours are offered twice a day. I dipped out of the tour after 45 minutes, having stood in the cold March wind on the terrace for a little too long. Hearing a very detailed account of the tactics and battle may not be for everyone. I’d have preferred a brief overview on a walk around the whole site.

But we saw a few hardy (or, perhaps, very polite) souls continue to the site of the abbey and stand in the rain, still listenening. True Anglo-Saxons, maybe.

The visitor centre offers a succinct 10-minute film which gives an easy-to-digest background to the battle if you prefer the broad brush approach to history.

The day I visited, the field itself was closed due to muddy, slippery conditions. I have walked it before and it is, frankly, to our eyes just a sloping field. It takes a powerful leap of imagination to visualise events of more than 950 years ago.

There were no eyewitness accounts of what happened on that October morning in 1066. But it somehow feels right to come here, to think about those who died – both those who were defending and those who were the vanguard of rulers who shaped our 21st century lives.

Admission

English Heritage members: free

Adult ticket: £12.90

Family ticket: £33.50 two adults, £20.60 one adult

Getting there by public transport

Train from Eastbourne, change at Hastings, takes 50 mins, plus 10 mins walk from station to Battle Abbey

:: The Eastbourne Reporter pays its way and reviews anonymously

Comments are welcome but they are pre-moderated

:: This kind of original journalism takes time to research and write but I want to keep it free to read – so please donate if you can. A regular subscription might even get you an occasional newsletter and some in-person events. Join a select group - support local journalism!

[kofi]